Law Practices and the Future of Work

Contents

Nicholas Poon*Nicholas is a director of Breakpoint LLC, a boutique law firm specialising in dispute resolution. Prior to founding Breakpoint LLC, Nicholas practised with Drew and Napier. He has also served in the Supreme Court as a Justices’ Law Clerk and an Assistant Registrar.

Talk about overhauling the practice of law in Singapore has been around for years stretching back to 2000. In truth, the landscape has changed but not by much, until very recently. The catalyst? The COVID-19 global pandemic. Overnight, law practices have been forced, by nature, to overhaul technology systems, work processes, to adapt to the unprecedented effects of a global pandemic. Will the industry build on the momentum of change? Or will we go back to our old and settled ways, as if the recent events are nothing more than an anomalous inconvenience?

I. INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 global pandemic has taught and shown the legal industry that it is capable of change and innovation. What we needed was a seismic push. The transformation that COVID-19 has begun still has a long way to run. But, another jolt from a continuation or worse still, repeat, of COVID-19 is the last thing anyone wants or needs. So, is this the end of our brief fling with transforming the face of legal practice?

Why must legal practice be transformed, one might ask. Is there really a need to reinvent the wheel when the system is evidently functional? Are we merely jumping on the transformation bandwagon for the sake of it?

At the end of the 20th century, Kodak, an American company, was one of the two global leaders of the film and photo business. The other was Fujifilm, a Japanese company. A substantial portion of their revenues came from selling films, and chemicals and paper that were needed to develop and print the photos captured on the films. The ‘silver halide’ strategy, as it was called after the chemical used to manufacture film, was the cornerstone of their empires.1Oliver Kmia, ‘Why Kodak Died and Fujifilm Thrived: A Tale of Two Film Companies’ (Peta Pixel, 19 October 2018) <https://petapixel.com/2018/10/19/why-kodak-died-and-fujifilm-thrived-a-tale-of-two-film-companies/> accessed 14 April 2020. Today, Kodak is a shadow of its former self.

Fujifilm, though thriving, is virtually unrecognisable from its past. The silver halide business exists to service a very niche and small group of film hobbyists.

Looking back now, twenty years later, it is obvious that the digital revolution of the 21st century would upend Kodak’s and Fujifilm’s core business. Indeed, to say that Kodak and Fujifilm did not see this day coming would be an overstatement. They both did. The difference between the two was, probably, vision.

Kodak saw light at the end of the photo industry tunnel and doubled down on its photo printing business. Fujifilm largely exited the photo industry which it considered to be fraught with competition and low profit margins, and pivoted into new business fields altogether, notably, in the medical space. As the pandemic rages on, Fujifilm’s influenza antiviral drug, Avigan®, was thrust into the global spotlight as a potential treatment for the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

II. THE THREAT TO LEGAL PRACTICE IS THE ABSENCE OF ONE

Unlike the photo industry in the 20th century, legal practice, as a subset of the legal services industry, is not facing an existential threat. Not yet, at least. Commentaries which assert otherwise frequently point to the encroachment by the ‘Big Four’ accounting firms into the legal services sector. It is thought that these accounting firm juggernauts, whose annual turnover dwarf the biggest global law practices by a factor of 10, have the resources to dominate the legal services landscape.

Undoubtedly, the accounting firms and their allied legal practices are here to stay. As David Wilkins of Harvard Law School observed, ‘clients want integrated solutions’.2Jonathan Derbyshire, ‘Bir Four Circle the Legal Profession’ Financial Times (London, 15 November 2018) <www.ft.com/content/9b1fdab2-cd3c-11e8-8d0b-a6539b949662> accessed 14 April 2020. A single problem may present tax, finance, management and information technology (‘IT’) issues on top of legal issues.3Derbyshire (n 2). So, law firms have lost and will continue to lose some business and clients to professional services outfits with multi-disciplinary offerings. But, it is quite another thing altogether to suggest that conventional law firms may be booted out of existence.

However, legal practice does face an existential threat – one that is stealthy, silent and lulls its target into a false sense of security. We, the lawyers responsible for legal practice, are our biggest threat. For the most part, we believe that legal practice is, as a service industry, immortal. Whatever shape or form it takes, legal practice is an indispensable facet of life. We continue to maintain this belief notwithstanding the recent events in Singapore which have called into question the essential nature of legal services.

This self-created and for some, self-fulfilling, idea of immunity from change, even as global political, economic and social structures are changing rapidly, halts introspection and reflection. It kills exploration and adventure. It limits innovation. It creates excuses for us to kick the can down the road for future generations. There is no impetus to worry about the future if one holds onto the view that the future is secure. It encourages and breeds short-termism.

In some ways, we are the SARS-CoV-2 virus to our own industry. Like the virus which uses spikes coated in sugars to disguise their viral proteins and help them evade the body’s immune system,4Chris Baraniuk, ‘Scientists Scan for Weaknesses in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein’ (The Scientist, 9 April 2020) <www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/scientists-scan-for-weaknesses-in-the-sars-cov-2-spike-protein-67404> accessed 14 April 2020. the relative macro-level stability and sense of permanence of legal practice have created for us ample and convincing justifications to sweep the deficiencies of legal practice under the carpet, as if they were present. As the virus has taught us, the absence of symptoms does not mean the absence of an infection.

III. OVERCOMING SHORT TERMISM

Short-termism is an innately human trait that can and does manifest in every facet of our lives. It is not confined to corporate boardrooms.5It appears that the term is generally used to refer to corporate conduct: Razeen Sappideen, ‘Focusing on Corporate Short-Termism’ (2011] SJLS 412. All things being equal, when given a choice, we tend towards instant or deferred gratification.

This human tendency has been amplified by the advent of the Instagram-world. 15-second TikToks; live videos on Instagram and Facebook; and playing videos at 1.5, 2 even 2.5 times faster than their original speed or fast-forwarding 8 to 10-second blocks on Netflix or YouTube – these are manifestations of our desire, even need, to consume information instantly and quickly. Whether we like it or not, the Too Long; Didn’t Read (TL;DR) age has arrived and is here to stay.

The need and longing for quick, easy gratification extends to the way we view our jobs. We are conditioned to expect reward for work done, which is fair. We expect that the reward should be commensurate to the work done, which is also fair. But, is this transactional relationship that we have with our jobs, where the focus is very much on what we can derive and extract from our jobs, causing us to blur out the people around us? Our clients? Our colleagues? Our fellow professionals? The future of the industry? Are we interested in leaving the industry in a better place for those who are to come after us?

Undoubtedly, saying that we should reinvest the law practice’s resources into building up the practice for future generations of lawyers who will pass through the doors is the easy bit. Talk is not only cheap, it is free. It ignores the harsh economic realities. Allocating the resources of a law practice – particularly financial resources – is a zero-sum activity. Putting aside a sum of money to purchase a high-end document storage solution system is taking away money which can be channelled towards current employees. This is a real conflict.

The challenge of finding that ideal balance is easy to underestimate. Some might be insurmountable for the foreseeable future. But this challenge, however tough, should still be confronted. Pretending or ignoring the challenge exacerbates the underlying problem, and does not make it go away.

It is not that law practices cannot survive by taking a year-by-year approach. They can, and they have thrived, precisely because many of us have been doing that. But, the costs of doing so is the entrenchment of mindsets, processes, systems and structures. Inertia is a powerful force.

When we see the tangible rewards of the fruits of our labour at the end of every month, quarterly, bi-annually or annually, it becomes easy to sell to ourselves the message that ‘The system works. Let’s not upset it by changing anything. Let’s not take the problems of the industry upon ourselves. We are too small. Let others with more resources lead.’ Over time, the illusory truth effect,6Emily Dreyfuss, ‘Want to Make a Lie Seem True? Say It Again. And Again. And Again’ (Wired, 11 February 2017) <www.wired.com/2017/02/dont-believe-lies-just-people-repeat/> accessed 5 May 2020. which amplifies the dangers of fake news, sets in. Little to no effort is spent on future planning and future-proofing the business. We eventually settle for familiarity over improvement. Surrendering to short-termism, although the easier option, is the gateway to a slow but sure eventual death of the law practice.

IV. AREAS OF UNDERINVESTMENT IN LEGAL PRACTICE

This discussion is not about paying a competitive wage. A competitive wage structure as a means of acquiring and retaining talent is important for the long-term viability of any business. That is the baseline. The discussion here concerns reinvesting profits of the law practice into structural features of the law practice – people, technology, processes – in the hope of generating higher net returns for the overall business.

Below are three key areas which law practices ought to pay more attention to.

A. Mental and emotional well-being of lawyers

Mental and emotional dysfunction is commonly regarded as a taboo subject in our Singapore society. This is even more so in legal practice. For a long time, we are told by our environment – the education system, family and relatives, and workplaces – that to be hardworking is a virtue, and hard work leads to success. All of this remains true, but what we need to do more, and be better at, is communicating failure and dealing with its effects. Because failure is real. Failure happens to everyone, even the best of us. No one is immune from setbacks.

Lawyers are not superhuman, as much as we like to think that we are. Ironic as it may seem to those outside of our profession, we are certainly not impervious to self-doubt, self-recrimination, and self-harm. When our jobs require us to absorb, make sense of, and ameliorate the collective trauma and pain experienced by others, it is normal, and indeed expected, that some of that trauma and pain will seep into our own lives. We should certainly strive for emotional disconnection as far as practicable, but we are only human.

For too long, law practices have turned a blind eye to mental and emotional well-being as a key aspect of legal practice. This is not a criticism of Singapore. It is a global phenomenon7Jarrod F Reich, ‘Capitalising on Healthy Lawyers: The Business Case for Law Firms to Promote and Prioritize Lawyer Well-Being’ (2019) 65(8) L Rev <https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3211&context=facpub> accessed 15 April 2020. which manifests itself in frequent inebriation and depressive states.8See Dreyfuss (n 6) 5. We need to start acknowledging, as a profession, that there is heavy price to pay in the quest for perfection. Seeking perfection is not the problem. Ignoring the spillover effects is. We can and should do more to speak of failure not as an end, but a direction. Failure is not failure if it results in actionable learning.9Amy C Edmondson, ‘Strategies for Learning from Failure’ (Harvard Business Review, April 2011) https://hbr.org/2011/04/strategies-for-learning-from-failure> accessed 2 May 2020.

It is not as if there is nothing that law firms can do to address mental well-being. From educating lawyers on how to cope with and redirect stress, to promoting healthy lifestyles, sports and well-being therapy sessions to professional counselling,10Sappideen (n 5) 34-37. concrete, practical solutions are easily implementable.

Tackling mental well-being head on is not merely the ‘right’ thing to do. It makes business sense. Lawyers are the most valuable resource of a law practice. Their productivity and effectiveness as lawyers are affected by their mental state. Lawyers who quit a cost to the law practice, even if it may not be apparent.11Leslie Larkin Cooney, Walking the Legal Tightrope: Solutions for Achieving a Balanced Life in Law (2010) 47 San Diego L Rev 421, 427. At a macro level, it is a huge pity, if not a waste of substantial private and public resources which were invested into educating and training lawyers, when lawyers quit the profession because they are unable to receive the holistic care that they need and deserve.

B. Productivity in core competencies

The second area which is perennially underinvested in is productivity in core competencies.

1. Lawyers generally

A lawyer is trained to provide legal advice. It is not just our first and foremost or principal capability. It is what distinguishes us from non-lawyers. Lawyers are no better – and in many cases, worse – than our non-lawyer colleagues at photocopying, binding, marketing, making presentation slides for pitches, trialing and implementing technology, proof-reading, generating bills, chasing payments and the like. These are all essential tasks and good people should be hired to perform these tasks. Not lawyers.

To the extent that it might be more efficient for lawyers to handle these tasks, for example, keying in billable time, the process should be made as seamless and effortless as possible. The use of software to allow lawyers to key in billable time on-the-go via mobile devices should be the norm. The law practice’s document storage system should enable lawyers to access any document remotely, on-the-go, reliably, and at any time of the day. Advanced PDF software should be available to all lawyers who may need to actively manage documents. The law practice’s collective institutional knowledge, particularly precedents, should be housed in a database that is easily searchable and accessible.

These are just some examples of process-management productivity gains for the taking. Beyond that is productivity in performing legal work. Be it research databases (both legal and non-legal), contract automation software, due diligence programmes, predictive and machine learning based simulations, or legal analytics, there is an assortment of technology solutions which are available to help lawyers be better lawyers.

2. Management of law practices

The running joke that lawyers are genetically wired to be numerically challenged might be in jest, but it must be true that there are non-lawyer professionals who are better at running law practices, as a business. Indeed, the diversion of time away from a senior lawyer at the top of his game to juggle management duties – finance, technology, human resource, operations – is almost certainly not the most productive use of the lawyer’s time. The time spent on management can always be better deployed, whether through self-improvement of one’s legal craft or mastering the materials needed to improve the quality of our core competency: lawyering. We are doing the law practice a disservice when we de-prioritise the exercise of our legal skills.

Our educational institutions have started designing courses aimed at equipping lawyers with business management and leadership skills. For instance, in 2019, the Future Law Innovation Programme, in conjunction with the Singapore Management University Academy, announced the launch of two new modules on design thinking and entrepreneurial ideation.12Cara Wong, ‘New Innovation Modules for Lawyers to Launch Next Month’ The Straits Times (Singapore, 31 January 2019) <www.straitstimes.com/singapore/new-innovation-modules-for-lawyers-to-launch-next-month> accessed 16 April 2020. The Singapore of Academy of Law has also partnered with INSEAD to offer leadership programmes to lawyers.13Singapore Academy of Law, ‘SAL-INSEAD Law Firm Leadership Programme’ (Singapore Academy of Law, 2020) <www.sal.org.sg/Resources-Tools/SAL-INSEAD-Law-Firm-Leadership-Programme/About-SILLP> accessed 9 June 2020.

These are positive developments for the industry. But, they are still predicated on lawyers calling and making the shots. The unique selling point or competitive advantage that lawyers have over non-lawyers is our technical ability to analyse and reason out legal issues. While some of these skills have universal application, we should not deceive ourselves into thinking that these skills somehow enable us to be as good as, if not better, managers than professional managers. Therefore, as far as practicable, law practices should strive to organise its business in such a way that lawyers focus on lawyering.14Michael A Hitt, Leonard Bierman and Jamie D Collins, The Strategic Evolution of Large US Law Firms (January 2007) 50 Business Horizons 17, 21-22.

It may be that there is a scarcity of professional managers in Singapore who understand the dynamics and intricacies of a legal practice. This is a speed bump, not a roadblock. The practice of law might be esoteric, but the business of delivering legal services is not. Moreover, professional managers are frequently not just specialists in the area that the company they are managing operate in. Their skillset lies in understanding the business model, where its strengths and pain points are, and devising optimal solutions to drive growth and value.

Of course, not every law practice needs or can afford to hire a top notch manager. There must be a certain size and scale to the operations of the business before the specialised skillsets of a professional manager will be value accretive to the law practice. But that should not stop smaller law firms from thinking about how they might be able to organise their business in a way that allows the lawyers to focus most of their time on legal work. A notable initiative in this regard is CLICKS@State Courts which offers co-working spaces with shared amenities and facilities so that law practices can focus on delivering legal services and worry less about facility management and operations.15Singapore Academy of Law, ‘CLICKS at State Courts’ (Singapore Academy of Law, 2020) <www.sal.org.sg/Resources-Tools/CLICKS-at-State-Courts/About-CLICKS> accessed 9 June 2020.

C. The model of work

Last but not the least, there is underinvestment in rethinking the model of work. This is especially important for the junior members of the profession – the so-called ‘Millennials’ and ‘Post-Millennials’.16According to Pew Research Center, millennials are born between 1981 and 1996, while those born in 1997 and later are post-millennials: Michael Dimock, ‘Defining Generations: Where Millennials End and Generation Z Begins’ (Pew Research Center, 17 January 2019) <www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/> accessed 15 April 2020.

The model of work which has worked well for the Boomers (born between 1946-1964) and Generation X (born between 1965 to 1980) may not work as well for Millennials and Post-Millennials. We have to start recognising, then accepting, the fact that Millennials and Post-Millennials were born into a very different epoch from those before them. Inevitably, their outlook, priorities and attitudes, shaped by their environment, will differ from those before them.

Perhaps the Boomers and Generation X are correct, that Millennials and Post-Millennials are ‘strawberries’ (because they bruise easily, like a strawberry). Perhaps the Boomers and Generation X are also correct to criticise the Millennials and Post-Millennials as lacking focus, drive, and stamina. But, what good does any of this do? At best, it accentuates the irreconcilability in attitudes across the different generations. At worst, it drives away the Millennials and Post-Millennials.

Law practices cannot afford to think that the terms are theirs to dictate. Gone are the days where legal practice is the place to be in. Boomers and Generation X did not have the luxury of dropping out of practice in their early years to join the ‘FANG’ gang – Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google, all of whom have swanky office setups, no dress codes, and canteens dishing out meals that can rival hotel caterers – and others like them as in-house counsel. Millennials and Post-Millennials do. Options are aplenty, even outside of the law.17Ankita Varma, ‘Legal Eagles Who Left Law for Other Career’ The Straits Times (Singapore, 14 February 2016) <www.straitstimes.com/lifestyle/legal-eagles-who-left-law-for-other-careers> accessed 16 April 2020.

Law practices need Millennials and Post-Millennials, and more of them as time progresses, whether they like it or not. Without a radical rethink of the model of work, how will law practices figure out how to attract and retain the best Millennial and Post-Millennial talents?

V. TEARING DOWN AND REBUILDING THE ECOSYSTEM TO PROMOTE STRATEGIC LONG TERM INVESTMENT

Rectifying structural underinvestment requires time and more importantly, capital: both political and financial.

Committing financial capital is the easy bit. Law firms, particularly but not limited to Big Law, are generally handsomely profitable. With the aid of productivity and efficiency-maximising technologies and processes, their profitability will only increase. There will be ample capital to redress the aforementioned underinvested areas.

The difficult part is coalescing political capital. Within the leadership, there will be a handful who are open, perhaps even prepared, to reinvent legal practice. But, that is not enough. The entire leadership and management must buy into the proposition that the future of their practices matter beyond their involvement. They must care enough to want to leave a better practice to the next generation. For transformation to take root, mindsets must change.

In August 1997, Steve Jobs announced to the world that Microsoft had agreed to invest US$150m into Apple which was, at the time, floundering. It was a watershed moment for two of the fiercest business rivals and, with the benefit of hindsight, humankind. The deal even found its way onto the cover of Time magazine. As Jobs explained, he realised that the notion that ‘for Apple to win, Microsoft has to lose’ was destructive for Apple, and ‘it was pretty essential to break that paradigm’.18Catherine Clifford, ‘When Microsoft Saved Apple: Steve Jobs and Bill Gates Show Eliminating Competition Isn’t The Only Way To Win’ (CNBC, 29 August 2017) <www.cnbc.com/2017/08/29/steve-jobs-and-bill-gates-what-happened-when-microsoft-saved-apple.html> accessed 16 April 2020. The rest, as they say, is history.

Of course, changing mindsets is not easy. But mindset change might be catalysed through the appropriate reform of the business and incentive structures. Two reforms are proposed here.

A. Reconceptualising the provision of legal services

Rajah & Tann Technologies is a shining albeit lonely example of what a bold vision might look like. An offshoot of Rajah & Tann Asia, Rajah & Tann Technologies offers six distinct technology solutions, including cybersecurity, contract management and data breach readiness and response. Naturally, many of the solutions offered complement the pure legal services offered by Rajah & Tann Asia or, indeed, any other legal practice. It is nonetheless a clear signal of Rajah & Tann Asia’s intentions to move beyond conventional legal services and offer its clients, and indeed competitors, expertise drawn from other disciplines.19Rajah & Tann Asia, ‘Rajah & Tann Launches Legal Technology Business’ (Rajah & Tann Asia, 16 November 2018) <www.rajahtannasia.com/news/news/media-release-rajah-tann-asia-launches-legal-technology-business> accessed 15 April 2020.

Of course, Rajah & Tann Asia is not the first or only business banking on multi-disciplinary offerings as the future of legal practice. As noted earlier, the accounting firms are the trendsetters in this regard. A multi-disciplinary approach, however, is not the only model of the future.

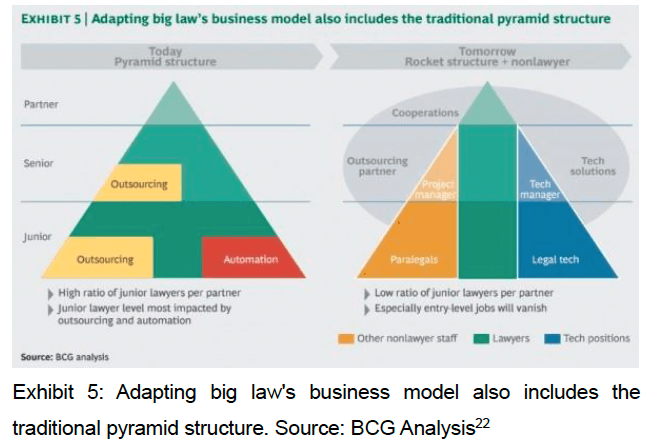

The Boston Consulting Group in collaboration with the Bucerius Center on the Legal Profession published in 2016 their take on the state and future of the legal industry.20Christian Veith and others, ‘How Legal Technology Will Change the Business of Law’ (Boston Consulting Group and Bucerius Law School, January 2016). Amongst their key predictions was a shift from the present pyramid structure to a ‘rocket structure’. The Chief Justice and Justice Kannan Ramesh have mentioned this in their speeches.21Sundaresh Menon, ‘Deep Thinking: The Future of the Legal Profession in an Age of Technology’ (29th Inter-Pacific Bar Association Annual Meeting and Conference, Singapore, 25 April 2019) <www.supremecourt.gov.sg/docs/default-source/default-document-library/deep-thinking—the-future-of-the-legal-profession-in-an-age-of-technology-(250419—final).pdf> accessed 15 April 2020; and Kannan Ramesh, ‘Keynote Address’ (Singapore Legal Forum 2019, Singapore, 24 August 2019). This model of the future law practice is illustrated in the follow graphic22Ivan Rasic, ‘From Pyramid to Rocket: How Legal Technology Will Change The Business of Law’ (Legal Tech Blog, 11 March 2016) <https://legal-tech-blog.de/from-pyramid-to-rocket-how-legal-technology-will-change-the-business-of-law> accessed 15 April 2020.:

As can be seen from the graphic, the future law practice envisioned is not a professional outfit offering the full array of professional services, of which legal services is one. The future law practice is made up of different departments, of which lawyers are but one. Other departments are staffed with specialists in their own right, whose work complements and supplements in equal proportion the legal services offered by the law practice. The future law practice will have distinct revenue streams, drivers, and cost centres.

Far-fetched though it may sound, it is not unthinkable that within the future law practice, a non-law service – for example, disclosure document management and analysis, legal skills and training, or project management – might be as, if not more, profitable than legal services, just as how frequent flyer programmes are amongst the most profitable units within airline companies. At one point, Qantas’ frequent flyer programme was three times as profitable as its international air aviation business and almost twice as lucrative as its domestic travel division.23Angus Whitley, ‘Qantas Frequent Flyer Program Turning Into Airline’s Biggest Money Spinner’ (The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 March 2017) <https://www.smh.com.au/business/companies/qantas-frequent-flyer-program-turning-into-airlines-biggest-money-spinner-20170512-gw34wq.html> accessed 16 April 2020. Who would have thought.

Again, not all law practices need to or can offer a suite of professional services. Not all legal practices need to or can transition their business into the ‘rocket structure’ model. But all law practices can think about their place in the future landscape and where they wish to stand in relation to the aforementioned models of practice.

It may sound and seem small, but being intentional in thinking of the future of the law practice is important. Intentional thinking forces us to ask questions, examine assumptions, test the evidence, and posit possibilities. Intentional thinking opens up minds.

B. Refreshing the regulatory framework governing ownership and management

Ever since the regulatory framework was changed to permit law practices to corporatise, law practices structured as corporations have been on the rise. One of the rationales given for allowing law practices to corporatise was to ‘encourage growth’ and ‘allow eventually for the formation of multi-disciplinary ‘one-stop’ professional corporations as well as encourage acquisition…of foreign law expertise’.24Singapore Parliamentary Debates: Official Report (10 March 1999) vol 70 at cols 395-396. The regulatory framework was amended following a comprehensive study and two reports by a Law Reform Committee, first in 199725Arfat Selvam and others, ‘Report of the Corporation of Professional Partnerships Sub-Committee’ (Singapore Academy of Law, 30 August 1997) <www.sal.org.sg/sites/default/files/PDF%20Files/Law%20Reform/1997-12%20-%20Corporatisation%20of%20Professional%20Partnerships_1.pdf> accessed 15 April 2020. and a follow-up in 1999,26Arfat Selvam and others, ‘Final Report of the Sub-Committee on Corporatisation of Law Partnerships’ (Singapore Academy of Law, 1 December 1997) <www.sal.org.sg/sites/default/files/PDF%20Files/Law%20Reform/1999-02%20-%20Corporatisation%20of%20Law%20Partnerships%20%28final%20report%29.pdf> accessed 15 April 2020. which was tasked to study the corporatisation of law partnerships.

Presciently, in its 1997 report which is the main report, the Committee noted:27Singapore Parliamentary Debates (n 24) para 10, 11.

The corporate structure is more suited for growth, for merger as well as reorganisation, as it is less tied down to the partners’ personalities. By depersonalising the practice, corporatisation also increases the willingness and ability to invest, in particular in high-tech equipment. On another level, the corporate structure offers opportunities for creating incentive or reward schemes for employees to have a stake in the company. An example is the giving of share options to retain as well as attract talent.

This was almost 23 years ago. Today, a law corporation still does not have all the rights and privileges of a regular company. Under the present regulatory framework, two notable limitations remain: (a) a limit on the number of shares and management voting rights of a law corporation that a non-lawyer can hold or control; and (b) a prohibition against non-practising lawyers holding shares in a law corporation. While seemingly innocuous, these two restrictions combined have chilling effects on long-term investment decision-making.

1. Restrictions on non-lawyer shareholding and management voting rights

Presently, non-lawyers can collectively own up to 25 percent of the shareholding28Legal Profession (Law Practice Entities) Rules 2015 (GN No S 480/2018) rule 37(2)(b). and control 25 percent of the shareholder voting rights of a law corporation.29ibid rule 3(1)(e). This is not negligible, and represents to some extent an improvement on the original proposal by the Committee.30Singapore Parliamentary Debates (n 24) para 24(c), where the Committee recommended that only practising lawyers be permitted to hold the office of a director. That being said, the Committee also recommended that non-lawyers can hold up to one-third (not just 25%) of the shares of the law corporation. However, it does mean that non-lawyers are and will remain a minority bloc, whether as a shareholder or within the Board.

The justifications for these restrictions were explained by Parliament in 2000 as necessary to maintain ‘high professional standards and protect[ing] the “interest of consumers”’.31Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Official Report (17 January 2000) vol 71 at cols 734-736 (Ho Peng Kee, Minister of State for Law). Why non-lawyer shareholders are assumed to be a drag on professional standards and consumer protection is, however, not clear.32It appears that the inspiration for the management voting rights restrictions and shareholder restrictions came from the Professional Engineers Act: Singapore Academy of Law ‘Final Report of the Sub-Committee on Corporatisation of Law Partnerships’ (n 25) footnote 11,12. However, interestingly, footnote 12 also noted that after amendments to the framework in 1995, the Professional Engineers Act ‘no longer imposes restrictions on shareholdings in limited liability engineering services corporation’. The previous restriction that non-engineers could only hold up to one-third of the shares was removed. Nonetheless, the result of these restrictions is that law corporations should still be primarily owned and run by lawyers.

Whatever may have been the thinking in 1997 or 2000 when the regulatory framework was amended, two decades have since passed. The world has changed remarkably. Globalisation aside, instant communications, data proliferation, cloud computing, have fundamentally altered personal and business behaviour. Lawyering remains a profession but the delivery of legal services, through a law practice, has become more layered, sophisticated, multi-dimensional. It is a business like any other.

In 2014, Singapore inched forward, ever so slightly. Headed by the Chief Justice, the Final Report of the Committee to Review the Regulatory Framework of the Singapore Legal Services Sector (‘Legal Services Sector Report’)33Sundaresh Menon and others, ‘Final Report of the Committee to Review the Regulatory Framework of the Singapore Legal Services Sector’ (Ministry of Law Singapore, January 2014) <https://app.mlaw.gov.sg/files/Final-Report-of-the-Committee-to-Review-the-Reg-Framework-of-the-Spore-Legal-Sector.pdf/> accessed 27 April 2020. advanced the disruption of the legal industry by, among other things, recommending a clear distinction between regulation of lawyers as professionals, and regulation of law practices as businesses;34Ministry of Law (n 33) para 64-65. recognising that other developed jurisdictions such as Australia and the UK have moved towards more liberal market-based equity ownership structures for law practices;35Ministry of Law (n 33) para 85. and postulating a gradual move towards permitting non-lawyers, even non-employees, taking a limited equity stake in law practices,36Ministry of Law (n 33) para 90. also known as the Legal Disciplinary Practice Model (‘LDP Model’).37The Final Report expressed a strong disinclination towards two other models, the multi-disciplinary practice or MDP Model i.e. which offers legal and extra-legal professional services, and the incorporated legal practice or ILP Model, which is basically the LDP Model and MDP Model but with the option of listing on a public stock exchange: see Ministry of Law (n 33), para 90.

Six years have passed since the Legal Services Sector Report was published. As mentioned above, the LDP Model is currently sanctioned under the present regulatory framework. However, it is unclear whether any law practice in Singapore has transitioned into a LDP Model and, if there are any, the extent of the shareholding that is held by non-lawyers. Most likely, the rate of adoption of the LDP Model is very low; if so, that only underscores how rooted short-termism is within the industry. More can, and must, be done to promote the LDP Model.

Indeed, looking ahead, there are good grounds to liberalise the LDP Model further.38The Legal Services Sector Report itself calls for the legal landscape to be reviewed every three years. Ministry of Law (n33) para 94. If the key personnel of the future law practice will comprise more than just lawyers; if the business of the future law practice comprises more than just providing legal advice and representation; if non-lawyers will be an integral part of future law practices; they will want to have a larger share and voice in the law corporation, and rightly so, to reflect their contributions to the success of the law corporation.

Law corporations should have the flexibility to decide how much shares and management voting rights can be given to non-lawyers. A cap of 25 percent of the profits through dividends from the shares and 25 percent of management rights for all non-lawyers collectively may be adequate for law corporations at the earlier stage of the transformation where the role of non-lawyers is still supportive and not materially accretive. It is less likely to be adequate for law corporations hoping to build a sizeable business around offering non-legal services and solutions.

VI. PROHIBITION AGAINST A NON-PRACTISING LAWYER HOLDING SHARES

The other restriction that should be reviewed is the prohibition against a non-practising lawyer from holding shares in a law corporation.39Legal Profession Act (Cap 161, 2009 Rev Ed) s1592(2) read with s 159(6), and based on Ministry of Law’s feedback. What this means is that lawyers who have been called to the Bar but are not in practice may not be shareholders of a law corporation. This also applies to lawyers who have never applied for a practising certificate, left practice midway or have retired from practice. It is the effect on the last group of lawyers – shareholders prior to their retirement – that is most damaging to long-term investment decision-making.

Lawyers can own shares in a law practice and typically, those who have a stake in the law practice are also involved in management. Consequently, the lawyer-shareholder should in theory have a vested interest in the firm’s long-term viability. But, this is not the reality because of the prohibition against non-practising lawyers holding shares in the law practice.

A key component of the value of shares in general lies in the shareholder’s ability to transfer the company’s shares for full value, that is to say, the company’s present value and future expected value. For instance, Apple’s share price is currently trading at 21 times its earnings. So, if Apple’s profits per share for this year is S$1, the full value which a participant in the market will pay to buy one share is S$21. A buyer who pays S$21 today is not just buying the right to receive a S$1 dividend (assuming all profits are returned to shareholders) for 21 years in order to recoup his investment. The buyer expects that Apple’s business will continue to grow, such that its long-term value will exceed S$21 so that at some point along the way, another person would be prepared to pay a higher amount for the shares.

If shares cannot be transferred from the existing shareholder to a new shareholder, those shares are illiquid and will be worth a lot less. The existing shareholder’s only prospect of recovering value from the company is through dividends from profits earned by the company. Now, that in and of itself is not a bad thing, if the shareholder is able to receive dividends for as long as the company is profitable and distributes its profit back to its shareholders.

However, that already depressed value declines substantially if a shareholder is compelled by law to dispose of his or her shares at some future point. Not only will the shareholder lose the value of all future dividends immediately, the shareholder has no bargaining position to transfer the shares for value to a third person. There is no incentive for the market to pay anything to take over the shares from someone who is prohibited by law from holding onto the shares.

Prohibiting lawyer-shareholders from holding onto shares upon ceasing practice thus effectively devalues the terminal value of their shares. At the point of retirement, those shares will effectively be worthless.

Now, one might say that this is fair. After all, underpinning the idea of law corporations ‘giving equity’ to a lawyer is the expectation that this new shareholder will contribute to the profits of the law corporation that are ultimately redistributed back to the shareholders. As a corollary, when the shareholder ceases practice and is by definition no longer contributing (directly at least) to the profits of the law corporation, the departing lawyer should not have rights to receive the future profits of the law corporation. Seen in this light, the regulatory framework which compels lawyers who cease practice to give up their shares goes hand-in-hand with the logic behind law corporations giving out equity to new shareholders. There is a downside cost, however.

In this regulatory framework, current lawyer-shareholders have no incentive to cause the law practice to reinvest the profits which would have been payable to them into funding long-term investments that are projected to deliver returns after they have retired from practice. Further, because retirement is not a matter of if but when, there is a finite timespan for sharing in the profits of the law corporation. Current lawyer-shareholders would therefore naturally desire and expect as much of the law corporation’s profits to be redistributed to shareholders each year, and every year.

There is no time, literally, to think about reinvesting into programmes which have no certainty of providing solid returns, or if they do, only well after the current shareholders have ceased being shareholders. In other words, under the current regulatory framework, underinvestment is all but guaranteed. The inertia observed is therefore entirely understandable, even expected.

Therefore, until the regulatory framework is reworked, and current lawyer-shareholders are given the option of reaping the benefits of any reinvestment of current profits long after they have ceased practice, it is likely that underinvestment in key growth areas will persist.

A. Partnerships

It is not just law practices structured as corporations which are disincentivised from making long-term investments. Partnerships organised around an agreement or understanding that partners relinquish all interest in the partnership’s profits upon retirement from the partnership suffer from the same disincentive. Underinvestment is endemic across the industry, probably because most law corporations and partnerships are organised on such terms.

VII. CONCLUSION

This short piece is not a scientific attempt to deconstruct the practice of law. It hopes to paint, in broad strokes, one perspective of the industry, where a few areas of improvement might be found, and the steps that could be taken to confront the challenges in those areas.

COVID-19 has upended nearly every business assumption, forcing businesses and governments to re-evaluate theories from monetary policy to healthcare sustainability and welfarism. The legal industry should do the same, reconsider the foundational truths of legal practice, rebuild or strengthen where necessary and feasible, so that we can liftoff for the next phase on a surer, stronger footing. As the adage goes, history is written by the winners.40Matthew Phelan, ‘The History of “History is Written by the Winners”’ (Slate, 26 November 2019) <https://slate.com/culture/2019/11/history-is-written-by-the-victors-quote-origin.html> accessed 14 April 2020. The management of Kodak and Fujifilm each had their own vision. It just happens that Fujifilm’s vision paid off, but not Kodak’s. And with that, Fujifilm’s vision is lauded and Kodak’s derided.